The

country that surrounds it, on both banks of the

Garonne, is the Agenais. Twenty-year-old city

established at the foot of the hillside of the

Hermitage which was the seat of the Gallic oppidum

of Nitiobroges, its history is intimately linked to

that of "Garonne", as the Agenais name their river

by personifying it. If it was nurturing and allowed

the development of trade, its many formidable

floods have given the city the reputation of being

the most flooded in France.

The

country that surrounds it, on both banks of the

Garonne, is the Agenais. Twenty-year-old city

established at the foot of the hillside of the

Hermitage which was the seat of the Gallic oppidum

of Nitiobroges, its history is intimately linked to

that of "Garonne", as the Agenais name their river

by personifying it. If it was nurturing and allowed

the development of trade, its many formidable

floods have given the city the reputation of being

the most flooded in France.

Today

protected by dikes, the city and its agglomeration

have largely spread in the valley. Agen has

preserved from its medieval past an important civil

and religious architectural heritage, enriched in

the late nineteenth century by the construction of

Haussmann-style buildings and houses Art Nouveau

and Art Deco during the piercing of broad

boulevards. The name of Agen is commonly associated

with the prune, whose production area is mainly

located in Lot-et-Garonne and which was formerly

shipped from the port of the city on the Garonne,

as well as in his club's rugby union. emblematic,

the SU Agen, which holds in particular 8 titles of

champion of France.

Economy

Agen's business is today essentially tertiary,

administrative and commercial. The city trip to

play, the main role of the average Garonne, ideally

located between the metropolises of Bordeaux and

Toulouse, developing and promoting trade (O'Green

Shopping Park, renovation of the heart of the

city), family tourism (Walibi South-West,

navigation on the side canal to the Garonne), or

the construction of a congress center and areas of

industrial and commercial activity (Agropole,

Technopole Agen Garonne).

History,

origins

The site of Agen was probably populated at least

since the Neolithic, but it is difficult at the

beginning of the hour. The remains that we

currently have at our disposal testify to a

settlement of Iberian origin to viiie and vii

centuries BC. However, the site occupied at that

time was different from the one we know today: it

is the plateau of the Hermitage. It is also this

situation (on a rocky outcrop) that would have been

the key to the toponymy of the city

The site, although located at the confluence of the

valley of the Mass and the Garonne, is not one of

the most strategic places of the valley. It is

therefore difficult to explain by geography alone

why the Nitiobroges (Celtic people who arrived

around 400 BC) chose this place as the capital of

their kingdom. They had built on this site a

stronghold of about 50 hectares, located 100 meters

above the bed of the Garonne. We found traces of

this occupation of the soil in the nineteenth

century and more recently, thanks to the work of

the team of archaeologists of the Agenais.

The displacement of the city towards the terraces

of the Garonne is undoubtedly anterior to the Roman

occupation. This transfer must be related to the

wealth of trade that took place along the river and

to the Pyrenees and the Massif Central. The

discovery of the very rich grave at Boé Char

is evidence of the opulence of local elites at the

end of the 1st century before Jesus Christ

Aginum,

Gallo-Roman city

The Gallo-Roman city has left important and quite

numerous traces. But most of them have been

destroyed and in particular the most interesting

ones. First of all, the theater, something quite

rare for a city of medium importance, especially

since Aginnum also had an amphitheater (dated 215

AD) that can accommodate 10,000 to 15,000 people.

considerable. There are also clues about the

existence of at least one necropolis. The city

stretched over 80 hectares and was therefore quite

rich and mostly populated. But prosperity was more

related to a transit activity than to a true

commercial pole. This intense passage is to be put

in relation with the early implantation of the

Christian religion. From the end of the third

century, the chronicles relate the martyrs of Saint

Caprais and Saint Foy, who would be buried on the

site of the present church of Martrou. In the

following century, the Christian Church organized

itself with its first known bishop, Phébade,

whose theological work earned him a prestige in all

of Christendom.

Agen

in the

"Moyen-Age"

Hover

over the images to enlarge them ...

As

with many cities, we have few records of the Great

Invasion era. For four centuries, Agen saw the

Vandals, the Visigoths and the Franks pass before

suffering the onslaught of the Vikings in the ninth

century. Historians have noted three invasions: in

843, 853 and the last in 922. The most destructive

invasion is that of 853. It is after this attack

that the relics of Saint Foy were taken to Conques,

probably between 877 and 884.

During the early Middle Ages, Agen remained in

Aquitaine near the Novempopulanie and the Duchy of

Vasconie. After the year 660, Vasconie and

Aquitaine became independent of the Franks and

reached their peak with Eudes d'Aquitaine. In 732,

the Saracens invaded the Vasconie and Bordeaux, but

their progress was stopped by Charles Martel and

Eudes between Poitiers and Tours. Pepin the Short

pursues the conquest of all Aquitaine and, in 766,

the Vascons, ancestors of the Basques (called

Wascones) went to Pepin Agen. The city fell back on

itself and fortified itself in its first enclosure

(about ten hectares) around the cathedral

Saint-Étienne (location of the current

market-covered parking) and whose foundation is

difficult to date. Having never been completely

finished, the building deteriorated and threatening

to collapse it was demolished in the early

nineteenth century.

It is around this nucleus that the medieval city

developed whose urban plot was organized from the

rue des Cornières (of which it remains a

part) which ended up Place du Marché (today

Place des Dairy). that is to say at the foot of the

old cathedral. The main vestiges of the medieval

Agen are religious buildings. We have already seen

that the Saint-Etienne cathedral has disappeared.

But the most magnificent monument is undoubtedly

the church of the Jacobins (today transformed into

a cultural center). The church is the last vestige

of the convent of the Jacobins (or Dominicans) and

dates from the thirteenth century. The

construction, with the exception of the three

central pillars (stone) separating the vessel into

two naves, is made of brick. Recent restoration

work has revealed murals depicting Alphonse de

Poitiers (lord of the city and protector of the

convent at its construction). It was the site of

great local or regional events: in 1354, the Black

Prince received the tribute of 40 barons and in

particular that of Gaston Phoebus.

The

city had a large number of other religious

buildings, convents or churches such as the current

cathedral: the collegiate Saint-Caprais, largely

Romanesque. Around the church was an architectural

ensemble to accommodate the canons: monastery,

cloister ... of which there remains only the

chapter house. Exploiting the feudal rivalries

between Plantagenet (succeeding the Counts of

Poitiers) and Counts of Toulouse and between Kings

of England and Capetian, bishops and inhabitants

could escape the tutelage of their lords.

From

the twelfth century, the city enjoys a certain

autonomy, it has a custom, freedoms and franchises.

This autonomy is confirmed in the thirteenth

century (the charter dates from 1248) and the

tutelage of the king (or the count) and the bishop

is more and more cowardly. The city is administered

by consuls who affix on the solemn acts the great

seal of the city representing on the obverse a

fortified city with inside a bell tower and on the

reverse an eagle. But the consular administration

is not democratic, it is an oligarchy that often

abused its powers, resulting in several popular

revolts in the following centuries.

The

city was indeed significantly enlarged during the

Middle Ages: it now reaches 60 hectares. Agen was a

prosperous and populated city (perhaps 10,000

inhabitants whereas Toulouse had less than 40,000)

living in particular activities related to the

Garonne: trade, fishing, milling. However, although

the city did not suffer too much directly from the

terrible clashes of the Hundred Years War (it even

gained a little more autonomy) it suffered the

consequences of the ravages of the surrounding

countries. In addition, the fourteenth and

fifteenth centuries experienced the terrible

epidemic of black plague aggravated by many and

devastating bad weather. The Garonne in particular

struck by deadly floods.

The

city was indeed significantly enlarged during the

Middle Ages: it now reaches 60 hectares. Agen was a

prosperous and populated city (perhaps 10,000

inhabitants whereas Toulouse had less than 40,000)

living in particular activities related to the

Garonne: trade, fishing, milling. However, although

the city did not suffer too much directly from the

terrible clashes of the Hundred Years War (it even

gained a little more autonomy) it suffered the

consequences of the ravages of the surrounding

countries. In addition, the fourteenth and

fifteenth centuries experienced the terrible

epidemic of black plague aggravated by many and

devastating bad weather. The Garonne in particular

struck by deadly floods.

The

time of the "Renaissance"

From the end of the Hundred Years War to the first

troubles of the wars of Religion, Agen experienced

a renaissance both material and intellectual. A

wave of immigration from the Massif Central, West

and Pyrenees repopulated the region. In addition,

the diocese was led by five successive Italian

bishops, many of them from the La Rovere family,

related to Pope Julius II. They were fine scholars,

like Mateo Bandello, author of short stories. This

is one of them, probably written at Bazens,

residence of the bishops of Agen, which inspired to

Shakespeare Romeo and Juliet. They came with a

whole suite of obscure people but also very

brilliant as the doctor and humanist Julius Caesar

Scaliger, known throughout Europe, or his son,

Joseph-Juste, acquired the Reformation (this is one

"illustrious" Agenais). Agen, a Catholic city (and

rival of Nérac, political and intellectual

capital of the Reformed), was repeatedly occupied

and looted by Protestant troops during this

dramatic period. It will shelter for some time the

Queen Marguerite de Valois, known as Queen

Margot.

The peace returned, the city knew a revival of

prosperity after a difficult Great Century, like

the rest of the country, because of climatic

conditions prejudicial to agriculture, activity of

which the city was very dependent. Popular

seditions, pestilences and famines mean that the

real return to prosperity did not take place until

the eighteenth century, which the numerous civil

buildings attest to: mansions of wealthy noble or

bourgeois families enriched in commercial and

textile activity. Only at the end of the century

was built the magnificent episcopal palace, which

later became the headquarters of the prefecture. At

that time, Agen was a manufacturing town

specialized in sailcloth but also sheets, ropes and

various fabrics. The city is leaving more and more

of its ramparts. She no longer fears the political

troubles but only the moods of the Garonne.

However, we do not hesitate to embellish the banks

of the river by developing the walk called "Gravel"

planted with abalone (now amputated and disfigured

by the path on the bank and the wall that now

separates the city from its river). This place was

home to major fairs, especially that of June where

barges came from all over Europe. The city is in

fact dependent more and more on its river which

exports to the Americas the flour of the High

Country that is exchanged there for sugar. Dried

plums are also sold to sailors who, during the

voyage, avoid scurvy. The wine trade was also very

important but hampered by the privilege of Bordeaux

wines prohibiting the sale of wines upstream until

Christmas, part of the production was transformed

into brandy.

Agen

in the XIXth

The Revolution then the continental blockade and

the beginnings of the industrial revolution will

bring heavy blows to the activities of Agen. But

this economic numbness that we see in the

nineteenth century is also to be put to the account

of the local bourgeoisie, which has lost its

dynamism and retreats to a less lucrative land

rent: the agricultural show of Agen 1855 seeks yet

to demonstrate the superiority of the fake on the

steering wheel! As Peter Weissberg wrote in the

history of Agen published by Privat in 1991: "Agen

has not missed its industrial revolution: it has

not even attempted." Thus, the assets that

constituted the railroad and the side channel of

the Garonne, which was, after transformation into

"canal of the two seas", according to the military

"to take half of the traffic of Gibraltar and to

avoid our fleet the humiliation to pass under the

English canons ", were insufficiently used or did

not see the light of day. The influx of people from

the Massif Central, the Pyrenees and Spain

compensated for the very large labor deficit in a

region in serious demographic decline but mainly

absorbed by construction and agriculture. The

nineteenth century, however, was one of great

achievements of the community. Since 1827, Agen

finally has a bridge (several attempts have

aborted, from the Middle Ages to the sixteenth

century and for 300 years we crossed the Garonne by

ferry), doubled by the bridge suspended in 1839 and

finally the canal bridge, completed in 1843 , a

masterpiece with 23 arches spanning the river and

its bed. It was in 1875 that the Garonne

experienced its most dramatic flood (it made 500

deaths in Toulouse and 8 in Agen) but the canal

bridge had resisted.

|

|

Hover

over the images to enlarge them ...

The

true transformations of the urban fabric of Agen

took place only under the mandate of Jean-Baptiste

Durand, between 1880 and 1895 (the city counted at

that time 20 000 inhabitants). The two main

boulevards were pierced today: République

and Carnot, the latter leading to the newly built

station (the main building was completed in 1858

and two side wings were added in 1886 and destroyed

in 1981). On the route of the old ramparts,

dismantled at the Revolution, belt boulevards were

made. These large sites, however, destroyed

testimonies of the past like most of the Sainte-Foy

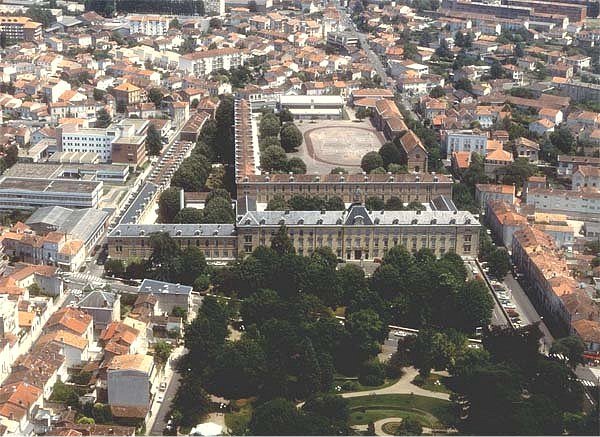

church. In 1888 is inaugurated the new high school

Bernard-Palissy d'Agen, built on a mound so that it

is safe from floods. The second high school of the

city (technical high school

Jean-Baptiste-de-Baudre, the name of the engineer

designer of the lateral canal) occupies the walls

of the major seminary, imposing building of the

late seventeenth century, built by Bishop Mascaron

to complete the work of the Counter-Reformation.

|

|

Hover

over the images to enlarge them ...

It

is finally Jean-Baptiste Durand who has built on

the site of the old cathedral the covered market,

in the style of the halls of Baltard, unfortunately

also disappeared. Fortunately, away from these

great works still remain small arteries, streets

and alleys with half-timbered houses and corbels or

old hotels of stone or brick. These buildings, the

oldest of which date back to the 14th century, give

Agen a particular cachet that can be found in other

cities of medium importance, sheltered from an

overly bulimic expansion.